Revista Iberoamericana de Neuropsicología

Vol. 4, No. 1: 28-43, enero-junio 2021.

Family Functioning in Parkinson’s Caregivers in Mexico and the US: Spanish Translation and Psychometric Refinement of the Score Family Assessment Questionnaire

Grace B. McKee, PhD.1,2, Paul B. Perrin, PhD.2,3, Jack Watson, BA.2, Mickeal Pugh, Jr., MA, MS.2,Duygu Kuzu, PhD.2,4, Teresita Villaseñor, PhD.5,6, & Sarah K. Lageman, PhD.7

1 Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness

2 Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

3 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Virginia Commonweath University

4 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Michigan

5 Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde

6 Master of Neuropsychology, Neurosciences Department, University of Guadalajara

7 Department of Neurology, Parkinson’s & Movement Disorders Center, Virginia Commonwealth University

Family Functioning in Parkinson’s Caregivers in Mexico and the US: Spanish Translation and Psychometric Refinement of the Score Family Assessment Questionnaire

Background: As healthcare for individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD) trends toward outpatient home settings, informal care is increasingly being provided by family members. While individuals with PD commonly experience decreased physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning, family caregivers also experience high burden and stress, in addition to associated mental health difficulties, all of which may impact family dynamics. Research is needed to examine family functioning within this population using appropriate measures. The purpose of this study was to validate the 15-item Systemic Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15), a short measure of family functioning, for use in families of individuals with PD in both English and Spanish. Method: PD Caregivers from clinics in Mexico (n = 148) and the US (n = 105) completed the SCORE-15. Results: Confirmatory factor analyses by site showed that neither sample evidenced a good fit to the original three-factor structure found in the SCORE-15. Exploratory factor analyses showed that for caregivers in the US, a similar three-factor structure was found to be the best fit. For caregivers in Mexico, a single factor emerged that reflected general unhappiness. All four new subscales showed acceptable internal reliability and good convergent validity. Discussion: Conceptualizations and assessment of family dynamics in the context of PD caregiving may have important differences in the US compared to Mexico. The use of measures, such as the adapted SCORE-15 from the current study, may help researchers and clinicians more fully capture families’ needs in the context of PD.

Key Words: Parkinson’s disease (PD); cross-cultural; family caregivers; Latin America; family functioning.

Antecedentes: A medida que la atención médica para las personas con la enfermedad de Parkinson (EP) se vuelca a entornos ambulatorios, los familiares asumen progresivamente el cuidado informal del paciente. Si bien las personas con EP suelen experimentar una disminución del funcionamiento físico, cognitivo y emocional, los cuidadores también experimentan una gran carga y estrés, además de las dificultades de salud mental asociadas al cuidado, lo que puede afectar a la dinámica familiar. Se requieren de más estudios que examinen el funcionamiento familiar dentro de esta población utilizando las medidas apropiadas para ello. Por tanto, el propósito de este estudio fue validar el “15-item Systemic Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation” (SCORE-15), una escala corta sobre el funcionamiento familiar, para su uso en familias de individuos con EP, tanto en inglés como en español. Método: Cuidadores de EP identificados en clínicas de México (n = 148) y E.E.U.U. (n = 105) completaron el SCORE-15. Resultados: Los análisis factoriales confirmatorios mostraron que ninguno de los grupos tuvo un buen ajuste a la estructura original de tres factores que se encuentra en el SCORE-15. Los análisis de factores exploratorios mostraron que para los cuidadores de los E.E.U.U. la mejor opción era una estructura similar de tres factores. Para los cuidadores de México, los análisis sugirieron un factor único que refleja la infelicidad general. Las cuatro nuevas sub-escalas mostraron una fiabilidad interna aceptable y una buena validez convergente. Discusión: Las conceptualizaciones y la evaluación de la dinámica familiar en el contexto del cuidado de la EP pueden tener diferencias importantes al comparar E.E.U.U. y México. El uso de medidas, como el SCORE-15 adaptado del estudio actual, puede ayudar a los investigadores y clínicos a captar de mejor manera las necesidades de las familias en el contexto de la EP.

Key Words: Enfermedad de Parkinson (EP); transcultural; cuidadores familiares; Latinoamérica; Funcionamiento familiar.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder1, and worldwide, 7-10 million people have a PD diagnosis2. With roughly 1 million Americans living with PD3, the disease represents a sizeable economic cost within the United States (US)—an estimated $14.4 billion in 20104. Incidence of PD in Mexico is estimated to be 9.48/100,000, though this number may be an underestimate5. Mexico spends roughly 8% less of its GDP than the US on healthcare6 with out-of-pocket expenses representing the bulk of total healthcare spending in Mexico7. Such a system may create difficulty in addressing the evolving needs of an aging and growing population, leading many individuals to avoid preventative care, delay seeking treatment, and relying on alternative or home remedies8.

As a degenerative movement disorder, PD is often characterized by tremors, rigidity, postural instability, bradykinesia, and gait disturbances9,10. Individuals with PD may commonly experience depression11, anxiety12, decreased life satisfaction13, and stigma14. In addition to the psychological consequences of PD, individuals may experience deficits in cognition ranging from mild15 to full dementia16, and, despite often having or requiring a significantly involved informal caregiver, they may experience feelings of isolation17. Caregivers can experience similar18 or worse19–21 mental health problems than the person for whom they care. Even though it can be a rewarding experience22, caregiving may have adverse health risks for informal caregivers23 and lead to poor health24. Specifically, PD caregivers experience high burden25, which is associated with depressive symptoms26 and lower life satisfaction27.

As healthcare trends toward an outpatient home setting, more responsibility is being placed on informal caregivers, who are often family members28. As such, it is important to study the factors and effects of PD within the family setting where the patient is embedded. One early study29 found the greatest burden of PD was personal, with family members expressing primary concern for the burden of caregiving and earnings loss. Perhaps most concerning, worse caregiver mental health predicted greater patient mortality for individuals with neurodegenerative disease30. Thus, it is of paramount importance for researchers and healthcare providers to understanding how PD may affect the family unit.

Burden can be affected by a variety of cultural and societal factors31. One specific factor that may be important, especially across different cultures, to understanding family dynamics for individuals with PD is the extent to which family needs are met. Families across both the US and Mexico report a need for health-related information32, with US families specifically requiring timely and intelligible information and knowledge that their loved one is receiving appropriate care33. In a study of Mexican caregivers for individuals with traumatic brain injury, another neurological condition, 69% or more of participants reported that health information needs were unmet. Similarly, 65% of participants indicated they did not have access to a medical professional within their community and were concerned about having enough resources to care for the patient32. Importantly, caregiver mental health was best when family needs were met32,34. With the close relationship between family needs and caregiver burden in mind, it is necessary to have an appropriate method to assess family functioning in the context of neurological conditions across cultures.

Current Study

Despite evidence of the impact of PD on the individual, caregiver, and on the family, to date there have been no known validation studies of measures of family dynamics within this group, and especially not in Latin America in Spanish. Stratton and colleagues35 developed the 15-item Systemic Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15), a commonly used measure of family functioning. In the development of the scale, which was shortened from the original 40-item version, the authors administered the measure to a convenience sample of non-clinical families in the United Kingdom and found a three-factor solution. The first factor, which the authors called Strengths and Adaptability, included items reflecting the family’s strategies for overcoming problems, taking care of each other, and general trust. The second factor, Overwhelmed by Difficulties, included items reflecting blaming tendencies, going from one crisis to another, and difficulties dealing with everyday problems. The third factor, Disrupted Communication, included items reflecting problematic communication styles, such as not telling the truth, ignoring other family members, and interfering in each other’s lives.

Although the SCORE-15 has been used in previous studies of families in clinical practice and non-clinical populations, there have been no known studies to date in families where one member has PD. Further, although the SCORE-15 has been validated for use in a number of languages, including Swedish36, Portuguese37, and Thai38, it has not yet been translated into Spanish or used in Spanish-speaking samples. It is unclear whether family functioning in Latin American countries comprises the same constructs as shown in the original three-factor structure presented by the SCORE-15 authors. It is possible that families in Latin America operate according to different cultural values or norms than the English-speaking families used to develop the original scale. The primary aim of the current study was to examine the scale’s psychometric properties and factor structure when administered in two samples of caregivers of individuals with PD. Data from one of these samples were collected in the US in English, and the second in Mexico in Spanish.

Participants

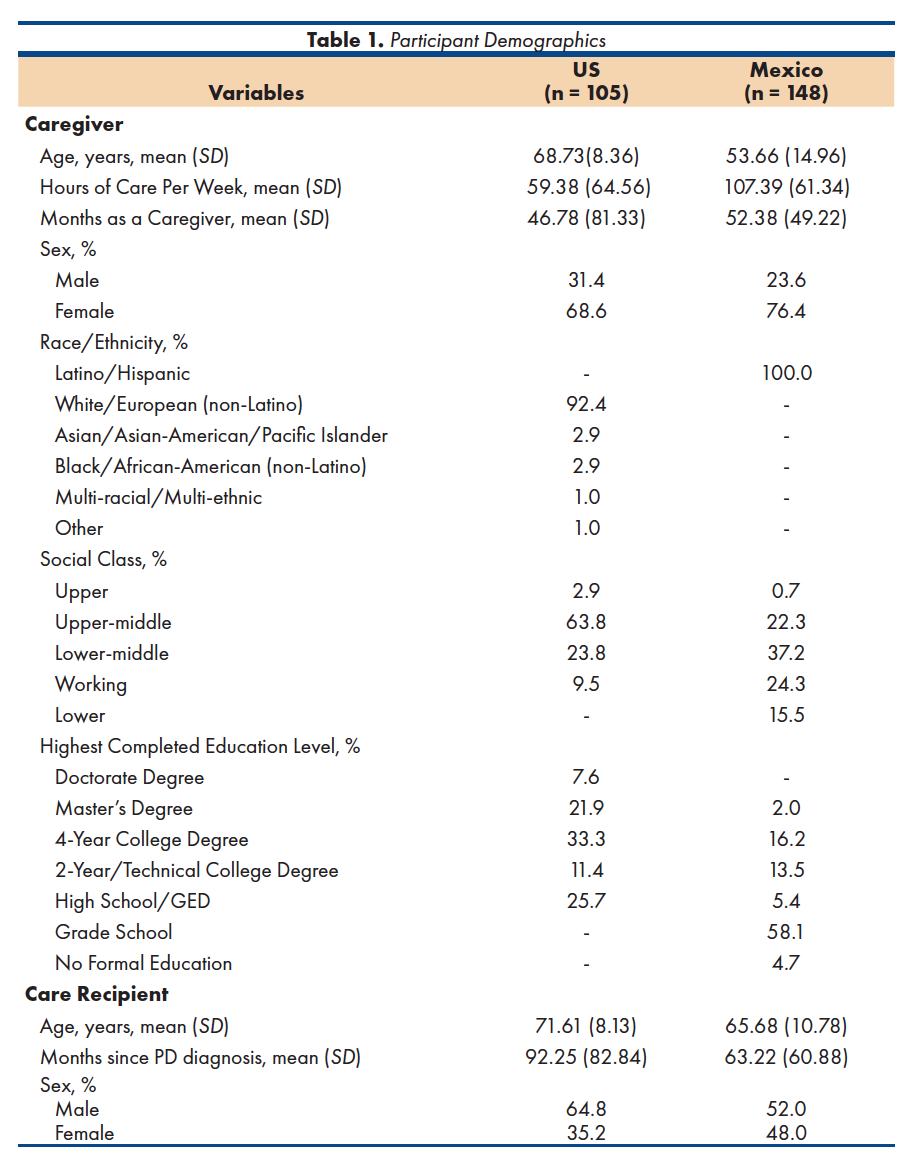

A sample of 253 informal caregivers of individuals with PD was recruited in the current study. The care recipient was enrolled at the Parkinson’s Clinic in the Hospital Civil Fray Antonio Alcalde, associated with the University of Guadalajara in Guadalajara, Mexico (n = 148) or from the Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Center of the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia, US (n = 105). Both of these medical centers were chosen for the current study data collection sites because they are located in public, urban academic medical centers, situated in state capitals (i.e., Guadalajara, Jalisco and Richmond, Virginia). To meet inclusion criteria, caregivers had to: (a) be the primary caregiver providing active daily care for a person with PD (b) who was currently being seen at the identified hospital, (c) be aged 18 or older, and (e) be able to communicate in Spanish (for the Mexico site) or English (for the US site). Demographic information for caregivers and the individuals with PD for whom they provided care appears in Table 1.

Procedure

PD caregivers were recruited from the hospitals in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico and Richmond, Virginia, US. Study materials and procedures were approved by an Institutional Review Boards at the participating universities in Mexico and the US. Caregiver eligibility was determined through a pre-screening, and if caregivers appeared to meet preliminary eligibility, a detailed review of the patient’s medical records was conducted. Eligible participants were given study information if they accompanied the patient to a medical appointment at either of the two clinics and provided informed consent. Study measures were orally administered at the Mexico site, given differing rates of literacy, whereas at the US site they were completed via paper and pencil. Participants did not receive financial compensation for participating in the study. The data for the current study were a part of a larger data collection effort that assessed demographic and psychosocial experiences of PD caregivers in the US and Mexico. Smith, Perrin, Tyler, Lageman, and Villaseñor39 conducted and presented a more detailed assessment of demographic and psychosocial site differences.

Measures

Family Functioning. The SCORE-1535 is a 15-item self-report questionnaire intended to assess outcomes in systemic family and couples functioning and is a derivative of the SCORE-40. Researchers suggested that the SCORE-40 appropriately assesses family functioning but has shown inefficiencies in clinical utility due to its length. The SCORE-15 is a quick and adaptable assessment tool that can be used in clinical settings. Participants are asked to rate the degree to which a statement describes their family functioning using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very well) to 5 (not at all). For the current study, the items forming the Strengths and Adaptability subscale were reverse-coded so that for all items, higher scores indicate more positive family functioning.

Psychometric properties of the SCORE-40 were originally assessed using a sample of 228 families and 510 original SCORE assessments. To factor analyze the 15-item version, researchers conducted a principal component factor analysis with a Varimax rotation. Results revealed four separate factors, but the fourth factor only had 2 items and was deleted. Strengths and Adaptability (e.g., we trust each other, we get listened to in my family), Overwhelmed by Difficulties (e.g., we seem to go from one crisis to another in my family, it feels miserable in our family), and Disrupted Communication (e.g., it feels risky to disagree in our family, people in my family are nasty to each other) formed the three-factor solution, and each factor consisted of five items. Research has shown strong internal consistency for the SCORE-1535 (Cronbach’s α = .89).

Because no Spanish version of this measure was available at the time of the study, the Chapman and Carter40 translation method was used to create a Spanish version. In this translation approach, a bicultural, bilingual researcher translated the original English version into Spanish, and a second bicultural, bilingual researcher back-translated this version into English. Any discrepancies in the translated versions were addressed. Both English and Spanish versions of the SCORE-15 are shown in Appendix A.

Symptoms of Depression. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-941) is a 9-item self-report measure assessing symptoms of depression in the previous two weeks. Participants respond to each item using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Nearly every day”). Responses are summed to form a total score, which ranges from 0 to 27, with higher scores reflecting greater symptoms of depression. In the current study, participants at the Mexico site completed the Spanish version of the PHQ-9. Previous research has shown that the PHQ-9 evidences good internal reliability in its original English form41 as well as the Spanish version42.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis by Country

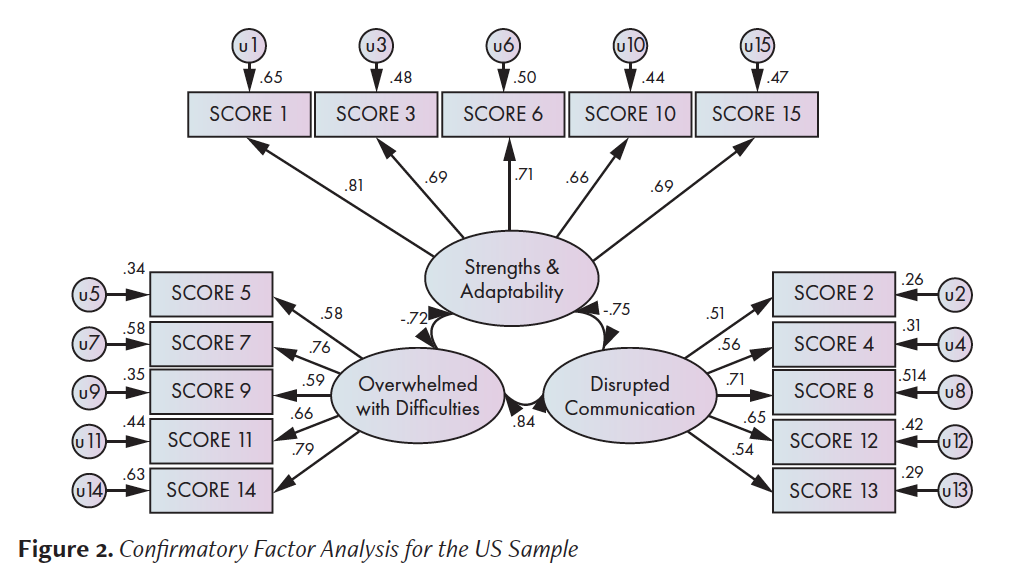

Two confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to test the fit of the SCORE-15 proposed three-factor structure separately for each country’s sample using IBM SPSS Amos 26. Each CFA contained the 15 items from the SCORE-15 as manifest variables. In addition, three latent constructs were tested which represented the three subscales of the SCORE-15. All latent factors were allowed to correlate.

CFA for Mexico Sample. Standardized item loadings and factor intercorrelations for this CFA can be found in Figure 1. The ꭓ2 goodness-of-fit test suggested that the original three-factor SCORE-15 solution was a poor fit to the data from the Mexico sample, ꭓ2 (87) = 156.59, p < .001. The root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) was .07; an RMSEA of .08 or less indicates good fit given the degrees of freedom43. However, the other measures of fit were all indicative of poor fit with the data. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) were .88, .89, and .83, respectively, where values greater than .90 are indicative of adequate fit. The comparative fit index (CFI) and normed fit index (NFI) were .89, and .78, respectively, where values above .95 indicate good fit.

CFA for US Sample. Standardized item loadings and factor intercorrelations for the US CFA can be found in Figure 2. The ꭓ2 goodness-of-fit test showed that the solution was a poor fit to the data, ꭓ2 (87) = 178.98, p < .001. The RMSEA was .10, above the .08 cutoff for good fit and at the cutoff of .10 for adequate fit43. The GFI, IFI, and AGFI were .82, .86, and .86, respectively, where values above .90 indicate adequate fit. The CFI and NFI were .85 and .76, respectively, where values above .95 indicate good fit. Overall, the fit indices suggest that the model for the US site evidenced poor fit to the data.

Exploratory Factor Analysis by Country

Because the fit indices for both samples generally suggested poor fit, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) assuming no a priori factor structure was conducted separately for each country’s sample in order to attempt to determine better factor structures for each site. Each EFAs were conducted using IBM SPSS 26. Models were estimated using principal axis factoring and a Promax rotation including all 15 items. After final factor structures were identified, Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for the total score and subscale scores. The subscales were then correlated with the PHQ-9 in order to examine convergent validity in the two samples.

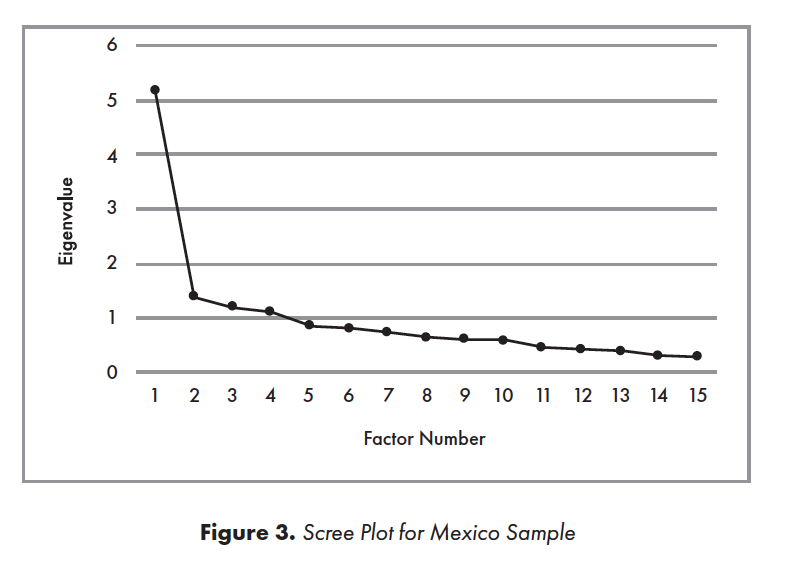

EFA for Mexico Sample. A scree plot44 (Figure 3) showed a pronounced inflection point at the second-highest eigenvalue, followed by a less-pronounced second inflection point at the fourth-highest. The first four factors explained 59.29% of the cumulative variance, in contrast to the fifth factor, which explained only an additional 5.66% of variance (initial eigenvalues). These small differences between the fourth and fifth factors suggested initial retention of four factors.

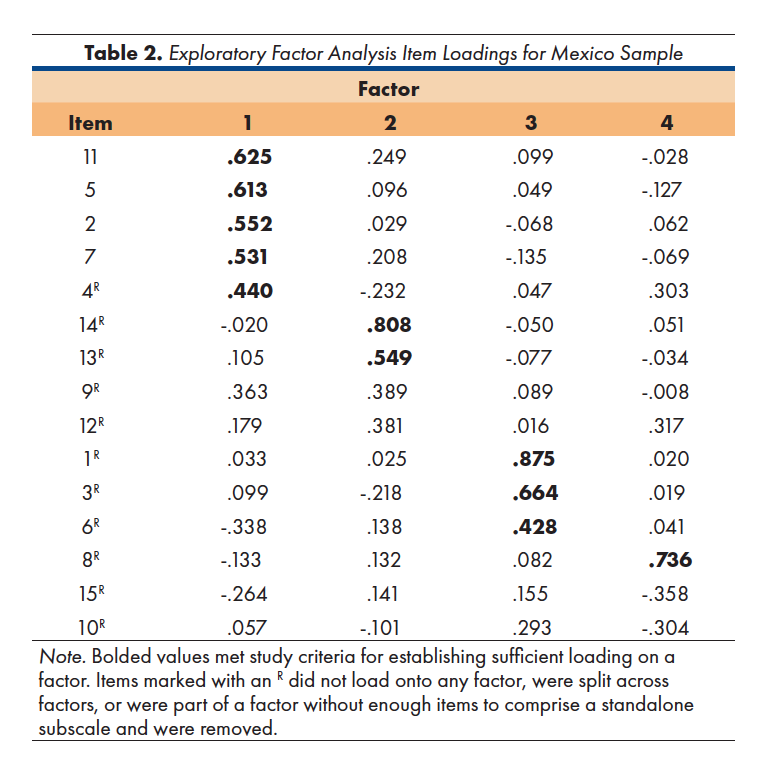

The item loadings for the first four factors in the Mexico sample appear in Table 2. In order to identify an item as loading meaningfully onto a factor, a simple structure approach was used wherein the loading on the primary factor had to achieve a magnitude of at least .40 with no secondary loading within a .15 magnitude difference of the primary loading. The four-factor structure found in this EFA bore little resemblance to the three-factor structure from the original scale. The first factor was comprised of three items from the original Overwhelmed by Difficulties subscale and one from the Disrupted Communication subscale. One item from the original Overwhelmed by Difficulties subscale and one from the original Disrupted Communication subscale loaded onto Factor 2. Factor 3 was comprised of two items from the original Strengths and Adaptability subscale. One item from the original Disrupted Communication subscale loaded onto Factor 4 and comprised the sole item for that factor. The remaining six items either did not load onto any factor or were split across two factors and were removed. Because factors comprised of fewer than three items are generally considered problematic45, Factors 2 (two items), 3 (two items), and 4 (one item) were removed. Only Factor 1 was retained. Appendix A denotes the items that loaded onto Factor 1 as well as the items that were removed.

In order to more appropriately characterize this single factor, the content of the items were examined in greater detail. The four items comprising this factor appeared to reflect the respondent’s own perceptions of broad unhappiness within the family (e.g., “it feels miserable in our family”), rather than associating specific behaviors with negative or positive functioning (e.g., blame, interference, listening). In order to reflect this, the single factor for the Mexico sample was called General Unhappiness.

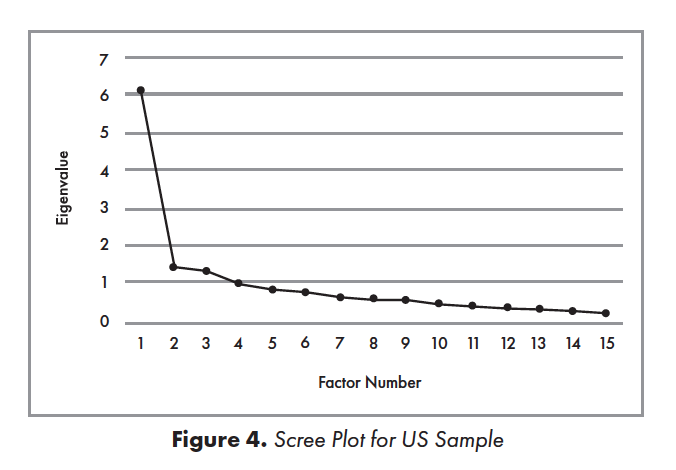

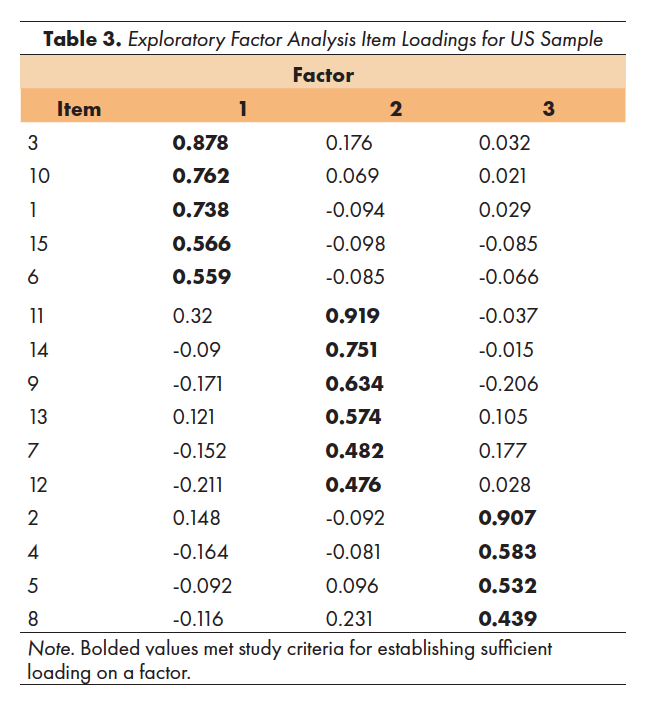

EFA for US Sample. A scree plot44 (Figure 4) showed a pronounced inflection point at the second-highest eigenvalue, followed by a less-pronounced second inflection point at the third-highest. The first three factors explained 59.32% of the cumulative variance, while the fourth factor explained only an additional 6.35% of variance (initial eigenvalues). These small differences between the third and fourth factors suggested initial retention of three factors.

The item loadings for the first three factors in the EFA for the US sample appear in Table 3. The three-factor structure found in this EFA and the three-factor structure from the original scale showed several similarities. All five items from the original Strengths and Adaptability scale loaded onto Factor 1, suggesting that all five should be retained. Four out of the five items from the original Overwhelmed by Difficulties scale loaded onto Factor 2, in addition to two items from the original Disrupted Communication subscale. The remaining three items from the original Disrupted Communication subscale showed highest loadings on Factor 3, along with the remaining item from the original Overwhelmed by Difficulties scale. Ultimately, three factors were retained, with one reflecting Strengths and Adaptability, and the other two reflecting general family pathology. Appendix A denotes the items that loaded onto each of these factors.

In examining the content of these two pathological subscales, the factors appeared to generally distinguish between active vs. passive family behaviors and patterns. Factor 2, for example, was comprised of several items indicating negative behaviors that family members actively utilize, such as blaming each other, interfering, and being nasty to one another. This factor was therefore named Maladaptive Strategies in order to reflect the problematic behaviors that family members may enact. In contrast, the third factor included items that might best be described as relating to avoidance or absence of positive behaviors, including not telling the truth, refraining from disagreeing, and inability to solve everyday problems, that could contribute to overall feelings of insecurity within the family. The content of these items suggest that this factor may be conceptualized as Barriers to Positive Functioning.

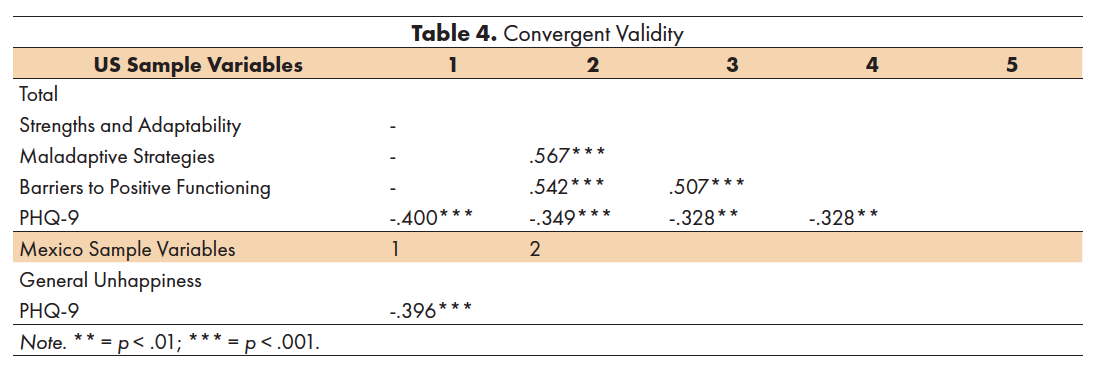

Reliability and Convergent Validity

In order to examine measures of internal consistency for the subscales resulting from exploratory factor analyses, Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for each subscale (three for the US site, one for the Mexico site) and for the overall US scale, since it was comprised of three subscales. Cronbach’s alphas for the Strengths and Adaptability subscale (US; α = .83), Maladaptive Strategies subscale (US; α = .83), Barriers to Positive Functioning subscale (US; α = .76), General Unhappiness subscale (Mexico; α = .74), and the total score (US; α = .90) were all adequate.

In order to examine convergent validity in the SCORE-15 subscales for both US and Mexico samples, SCORE-15 subscale scores and the US total score were correlated with the PHQ-9. All correlations among the US subscales as well as between all SCORE-15 subscales and the PHQ-9 were highly significant, suggesting strong convergent validity (Table 4).

The aim of the current study was to examine the factor structure of a measure of family functioning in two samples of PD caregivers from the US (n = 105) and Mexico (n = 148). Although the SCORE-15 is a commonly used measure and has been translated into a number of languages, to date it has not been translated or validated for use with a Spanish-speaking population. This study is the first known to administer this measure in samples of PD caregivers and to validate its use with individuals who speak Spanish. Results from CFAs showed that data from neither sample demonstrated good fit with the original three-factor structure reflecting Strengths and Adaptability, Overwhelmed by Difficulties, and Disrupted Communication. In general, the factor loadings for both samples tended to be lower than those found in the original scale development article. Moreover, for the Mexico sample, two item loadings in the original Disrupted Communication subscale were below .40. Overall, these results suggested that the original three-factor structure did not hold well for these two samples of PD caregivers.

Subsequent EFAs showed that for the US sample, a slightly different but similar three-factor structure appeared to be the best-fitting solution. Within this factor model, the same Strengths and Adaptability factor emerged, but the remaining two factors were each comprised of items from the two other original subscales. This finding may indicate that for US PD caregivers, the construct of Strengths and Adaptability still holds, but that constructs reflecting types of pathology may differ from families in the original sample. Specifically, the structure found in the current study distinguished between more active negative behaviors (Maladaptive Strategies) and avoidance or absence of positive behaviors (Barriers to Positive Functioning), in contrast to the Overwhelmed by Difficulties and Disrupted Communication factors found in the original scale development study. These three subscales and the total score showed acceptable to good internal reliability as well as strong convergent validity with the PHQ-9.

In contrast, results from the EFA in the Mexico sample showed a one-factor structure. Although a total of four factors were initially extracted, three of these were discarded due to too few items after removing items that were split across factors. The remaining factor contained items reflecting one’s perception of general unhappiness within the family, while items reflecting specific negative and positive behaviors were among those removed. This single subscale demonstrated acceptable internal reliability and strong convergent validity with the PHQ-9. Overall, these results suggest that the three-factor structure of family functioning found in the initial sample of non-clinical UK families may not hold in samples of PD caregivers in Mexico. Instead, a one-factor structure of a short form containing these items reflecting general unhappiness may more closely reflect functioning in these families.

Although the participants at the Mexico site completed a version of the SCORE-15 that was translated into Spanish, it may be that the SCORE-15 does not accurately assess the construct of family functioning in populations outside of Western Europe and the United States. It could be that within Latin American families affected by PD, there may be more salient indicators of family functioning that were not adequately covered by the items as they are currently written. The Latin American cultural values of familismo, which refers to one’s identity as a member of the family unit46, and interdependence, where individual goals are superseded by the family’s best interests47, have collectivist roots that may not be reflected in this measure developed with UK families. From this lens, some of the items in the SCORE-15 may not fully capture the construct of family functioning within this cross-cultural context. Moreover, specific behaviors such as interference, blaming, and avoidance of disagreements were not included in the single factor that emerged from the Mexico sample, which could provide additional evidence for cultural specificity in family functioning. For example, the item assessing for interference in family members’ lives may not be sensitive enough to distinguish culturally acceptable vs. unacceptable levels of interdependence within the family unit. When viewed from a Eurocentric lens in which individualism is prioritized, interdependence may be conceptualized as an indicator of pathology; in contrast, in a more collectivist culture, similar behaviors could be indicative of normative functioning.

Clinical Implications

The results of the study indicate several important clinical implications. Because familismo is a core value in Latino cultures48, family-centric interventions with scales sensitive to cultural patterns are needed. For this reason, using the factor structures found separately in Spanish and English in the current study may be helpful for assessing family functioning which would be more culturally sensitive to therapeutic change. Even though the SCORE-15 has been translated into a number of other languages, it has not previously been studied with this clinical population. In addition, the scale was developed with non-clinical families from the UK, whose Eurocentric norms may emphasize different cultural values from those in Latino cultures. Having measures available in Spanish that are sensitive to these cultural values may allow data collection among Spanish-speaking caregivers which can contribute to the development of empirically supported treatments.

The current study may also provide guidance to marriage and family therapists and rehabilitation clinicians as to how well this Eurocentric construct may apply to their patients, especially individuals with chronic health conditions like PD. In conjunction with previous research which has identified that caregivers who have high family satisfaction and cohesion show higher life satisfaction and lower caregiver burden34, the results from the current study underscore the necessity of using a systems approach in clinical work with these families. Thus, change in health status or symptoms in one family member can substantially impact the functioning of other members individually, as well as family dynamics as a whole. Taking into consideration possible cross-cultural differences and utilizing a family-systems approach may help clinicians refrain from pathologizing certain types of patterns and interactions common to Latino cultures. Additionally, it would be useful to monitor progress in family therapy with the new factor structures of the SCORE-15 from beginning to the end in order to show improvement during sessions to patients, or to facilitate early detection of worsening family functioning.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results from the current study should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations, which also provide directions for future research in this area. First, the samples were limited in both size and participant characteristics. Data were collected from two large cities in the US and Mexico which limits generalizability to other areas of each country or global region. Future research would benefit from collecting data from more geographically diverse samples of participants in order to more fully capture any regional differences that may affect results. Further, additional research should attempt to collect data from caregivers in other Latin American countries or from caregivers in the US who identify as Latino in order to improve generalizability.

There were also a number of site differences between the US and Mexico samples, explored in greater depth in a previous study39, that may have affected the pattern of results found in the current study. Most caregivers in the US sample (92.4%) identified as White/European (non-Latino), in contrast to the caregivers in the Mexico sample where 100% were Latino/Hispanic. Caregivers in the US sample had higher education levels and socioeconomic statuses than those in Mexico, as 29.5% reported completing a graduate degree and two-thirds belonged to upper-middle or upper classes. In contrast, only 2% of caregivers in Mexico reported completing a graduate degree, while most (58.1%) had attended grade school only. Moreover, caregivers in the US sample reported higher education levels and socioeconomic statuses than the general US population. Future research would benefit from including a more diverse sample of US participants in terms of race/ethnicity, education levels, and socioeconomic status or income in order to contribute to more accurate cross-cultural comparisons of PD caregivers and their family needs.

The current study investigated the use of the SCORE-15, a measure of family functioning, with PD caregivers in the US and Mexico, in order to examine whether the original three-factor structure would still hold. This original structure was found to be a poor fit for the data in both samples. For caregivers in the US, a similar three-factor structure was found to be the best fit; this structure retained the first factor reflecting Strengths and Adaptability, but two other distinct factors emerged reflecting Maladaptive Strategies and Barriers to Positive Functioning. For caregivers in Mexico, a single factor emerged that reflected perceptions of general unhappiness, while most items did not load on any factor. Conceptualizations and assessment of family dynamics in the context of PD caregiving may have important differences in the US compared to Mexico. The use of measures, such as the adapted SCORE-15 from the current study, may help researchers and clinicians more fully capture families’ needs in the context of PD.

- de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(6):525-535. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9

- Parkinson’s Foundation. Statistics. Published 2017. https://parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Statistics

- Mahajan A, Balakrishnan P, Patel A, et al. Epidemiology of inpatient stay in Parkinson’s disease in the United States: Insights from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;31:162-165. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2016.03.005

- Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, Storm MV, Jain A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the United States: Economic burden of PD in the US. Mov Disord. 2013;28(3):311-318. doi:10.1002/mds.25292

- Rodríguez-Violante M, Velásquez-Pérez L, Cervantes-Arriaga A. Incidence rates of Parkinson’s disease in Mexico: Analysis of 2014-2017 statistics. Rev Mex Neurocienc. 2019;20(3):2253. doi:10.24875/RMN.M19000043

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance. Published online 2000.

- Pagán JA, Ross S, Yau J, Polsky D. Self-medication and health insurance coverage in Mexico. Health Policy. 2006;75(2):170-177. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.03.007

- World Health Organization. The benefits and risks of self-medication. WHO Drug Inf. 2000;14(1):1-2.

- Alves G, Forsaa EB, Pedersen KF, Dreetz Gjerstad M, Larsen JP. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2008;255(S5):18-32. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-5004-3

- Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(16):1130-1143. doi:10.1056/NEJM199810153391607

- Gotham AM, Brown RG, Marsden CD. Depression in Parkinson’s disease: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49(4):381-389. doi:10.1136/jnnp.49.4.381

- Menza MA, Robertson-Hoffman DE, Bonapace AS. Parkinson’s disease and anxiety: Comorbidity with depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34(7):465-470. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(93)90237-8

- Gustafsson H, Nordström P, Stråhle S, Nordström A. Parkinson’s disease: A population-based investigation of life satisfaction and employment. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(1):45-51. doi:10.2340/16501977-1884

- Burgener SC, Berger B. Measuring perceived stigma in persons with progressive neurological disease: Alzheimer’s dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Dementia. 2008;7(1):31-53. doi:10.1177/1471301207085366

- Litvan I, Goldman JG, Tröster AI, et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):349-356. doi:10.1002/mds.24893

- Emre M. Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2(4):229-237. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00351-X

- Martínez-Martín P. An introduction to the concept of “quality of life in Parkinson’s disease.” J Neurol. 1998;245(S1):S2-S6. doi:10.1007/PL00007733

- Budh CN, Österåker A-L. Life satisfaction in individuals with a spinal cord injury and pain. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(1):89-96. doi:10.1177/0269215506070313

- Raj JT, Manigandan C, Jacob KS. Leisure satisfaction and psychiatric morbidity among informal carers of people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(11):676-679. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101899

- Weitzenkamp DA, Gerhart KA, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Savic G. Spouses of spinal cord injury survivors: The added impact of caregiving. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(8):822-827. doi:10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90194-5

- Dreer LE, Elliott TR, Shewchuk R, Berry JW, Rivera P. Family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: Predicting caregivers at risk for probable depression. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52(3):351-357. doi:10.1037/0090-5550.52.3.351

- Henriksson A, Carlander I, Årestedt K. Feelings of rewards among family caregivers during ongoing palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1509-1517. doi:10.1017/S1478951513000540

- Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Fox P, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1006-1014. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30103.x

- Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study: An ancillary study of the cardiovascular health study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):110-116. doi:10.1007/BF02883327

- Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B, et al. Caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(7):924-931. doi:10.1002/mds.21355

- Clyburn LD, Stones MJ, Hadjistavropoulos T, Tuokko H. Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer’sdisease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(1):S2-13. doi:10.1093/geronb/55.1.S2

- Manskow US, Friborg O, Røe C, Braine M, Damsgard E, Anke A. Patterns of change and stability in caregiver burden and life satisfaction from 1 to 2 years after severe traumatic brain injury: A Norwegian longitudinal study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;40(2):211-222. doi:10.3233/NRE-161406

- Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(4):213-231. doi:10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213

- Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan F, Kulas E, Cutson T, Schenkman M. The burden of Parkinson’s disease on society, family, and the individual. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(7):844-849. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01512.x

- Lwi SJ, Ford BQ, Casey JJ, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(28):7319-7324. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701597114

- Lim YM, Luna I, Cromwell SL, Phillips LR, Russell CK, de Ardon ET. Toward a cross-cultural understanding of family caregiving burden. West J Nurs Res. 1996;18(3):252-266. doi:10.1177/019394599601800303

- Doyle ST, Perrin PB, Díaz Sosa DM, Espinosa Jove IG, Lee GK, Arango-Lasprilla JC. Connecting family needs and TBI caregiver mental health in Mexico City, Mexico. Brain Inj. 2013;27(12):1441-1449. doi:10.3109/02699052.2013.826505

- Price DM, Forrester DA, Murphy PA, Monaghan JF. Critical care family needs in an urban teaching medical center. Heart Lung J Crit Care. 20(2):183-188.

- Perrin PB, Stevens LF, Sutter M, et al. Exploring the connections between traumatic brain injury caregiver mental health and family dynamics in mexico city, mexico. PM&R. 2013;5(10):839-849. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.05.018

- Stratton P, Bland J, Janes E, Lask J. Developing an indicator of family function and a practicable outcome measure for systemic family and couple therapy: the SCORE: Systemic family and couple therapy. J Fam Ther. 2010;32(3):232-258. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00507.x

- Zetterqvist M, Hånell HE, Wadsby M, Cocozza M, Gustafsson PA. Validation of the Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE‐15) self‐report questionnaire: index of family functioning and change in Swedish families. J Fam Ther. 2020;42(1):129-148. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12255

- Vilaça M, de Sousa B, Stratton P, Relvas AP. The 15-item Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15) scale: Portuguese validation studies. Span J Psychol. 2015;18:E87. doi:10.1017/sjp.2015.95

- Limsuwan N, Prachason T. The reliability and validity of the 15‐item Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE‐15) Thai version. J Fam Ther. 2020;42(1):119-128. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12248

- Smith ER, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, Lageman SK, Villaseñor T. Parkinson’s symptoms and caregiver burden and mental health: a cross-cultural mediational model. Behav Neurol. 2019;2019:1-10. doi:10.1155/2019/1396572

- Chapman DW, Carter JF. Translation procedures for the cross cultural use of measurement instruments. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1979;1(3):71-76. doi:10.3102/01623737001003071

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Arrieta J, Aguerrebere M, Raviola G, et al. Validity and utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2 and PHQ-9 for screening and diagnosis of depression in rural Chiapas, Mexico: A cross-sectional study: PHQ-9 validity for depression diagnosis. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(9):1076-1090. doi:10.1002/jclp.22390

- Meyers L, Gamst L, Guarino A. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation. 3rd ed. Sage; 2017.

- Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar Behav Res. 1966;1(2):245-276. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

- Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10:1-9.

- Niemann, Y. F. Stereotypes of Chicanas and Chicanos: Impact on family functioning, individual expectations, goals, and behavior. In: Velasquez RJ, Arellano LM, McNeill BW, eds. The Handbook of Chicana/o Psychology and Mental Health. Laurence Erlbaum Associates; 2004:79-100.

- Santiago-Rivera, A. L., Arredondo, P., Gallardo-Cooper, M. Counseling Latinos and La Familia: A Practical Guide. Vol 17. Sage; 2002.

- Villarreal R, Blozis SA, Widaman KF. Factorial Invariance of a Pan-Hispanic Familism Scale. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2005;27(4):409-425. doi:10.1177/0739986305281125